Wearing pants has been optional for the QuickStar crew this past year, and more often than not we have opted out. Our endless summer has aided the pursuit of this state of undress and the limitation of fresh water for regular washing has justified it. Humbolt Squid, as the youngest crew member, has revelled more than most in his state of pantlessness, swinging freely from halyards in his undies; there are many more important things on which to spend one’s time each day than getting fully dressed. The absence of pants is just part of the heightened level of freedom that Squid and Dolphin have been blessed with this year, allowing them the uncommon privilege of a less structured childhood experience.

Childhood affords us many freedoms as we glide through life blissfully unmindful of anything that exists outside our pivotal point of reference - our own self. It is a time when we are unhindered by the constraints of responsibility and societal expectations, but with no knowledge that these things exist we can’t yet fully appreciate the joyous freedom that is temporarily ours. Childhood is a unique time of unencumbered exploration, where a future adult’s views of the world and their place in it are formed. Ideally a child would be set loose to determine their own path and make mistakes along the way, but that doesn’t always happen these days. Children are scheduled with military precision into an array of suitably supervised activities with predetermined outcomes. Their goals are decided for them and how they will be achieved is carefully laid out. Skills are acquired, but not organically, so some of the truest experience of learning is lost.

While we have been away, there have been no swimming, drama, music or dance lessons, weekly soccer training or taekwondo is a distant memory and not a single scheduled weekend sporting activity has been present in our lives. Yet our children have danced barefoot with old cultures, learned the beat of traditional songs, swum hard to keep up with giant manta rays and tumbled through schools of tropical fish. They have carried soccer balls to remote villages and taken off their shoes to run and play with the local children. They have rowed the dinghy ashore on their own, armed with a bottle of water, a VHF radio and independence, their only instructions being to play. They now say with confidence and calmness, “I’m taking the SUP out for a paddle”, knowing they are free to explore the bay where we have anchored. These are not one off instances, but form the general ebb and flow of their lives. They have been free to wander, making mistakes along the way and seeing how their actions have consequences. They have achieved much, and feel good about themselves despite the absence of plastic trophies.

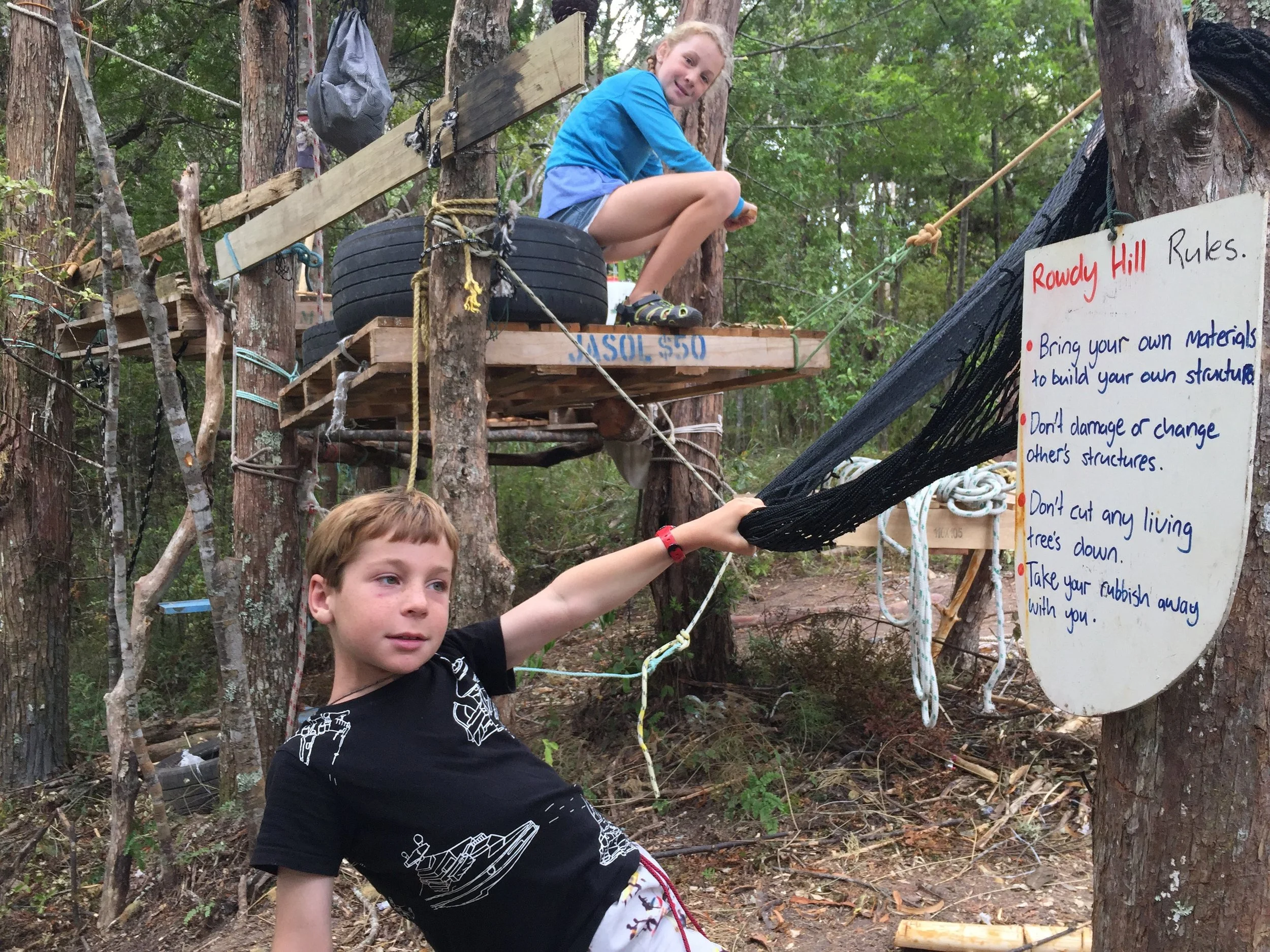

Rowdy Hill sums up this type of childhood existence. The water children of a Northland sailing village have created their own secret village in the hills. Roles are defined; Dolphin is the carver, using the multi-tool she proudly bought with her pocket money, and Squid is the shop assistant trading in a currency of silver ferns. They have come up with four simple rules governing the village, attached to a tree on display for all to see. They are born from their experience of what creates a harmonious society and the need for some shared values to be agreed in order for Rowdy Hill to function: 1 Bring your own materials to build your own structure; 2 Don’t damage or change other’s structures; 3 Don’t cut down any living trees; 4 Take your rubbish away with you. The children are left to their own devices, designing the village, gathering the materials needed and working together to achieve the goals they have set themselves. Dolphin sighed deeply at the end of a day of construction, acknowledging how hard it was to get design consensus; she was not complaining, just noting the life lesson she had learned. Squid returned enraged another day, barely able to express his anger at a live tree being cut down for one of the shelters. These experiences found their way into the Rowdy Hill Constitution. Left to learn in freedom and without adult guidance, these children have done well, they have done very well.

I’m not sure where my children will sit amongst the graded order of numeracy skills and swimming levels when we return to Sydney. Perhaps I have failed dismally at imparting problem solving algorithms learned by rote to get them through maths tests, and although their underwater swimming is strong, it might not fit with the requirements of the Marlin swim class. But I think they have gained the skills needed to help themselves find a means to fill in the gaps that are important to them. Their year without pants has upskilled them in ways a classroom could not and I hope that in years to come they will look back affectionately on this time of freedom and learning.